If you haven't already, click here to read part 1

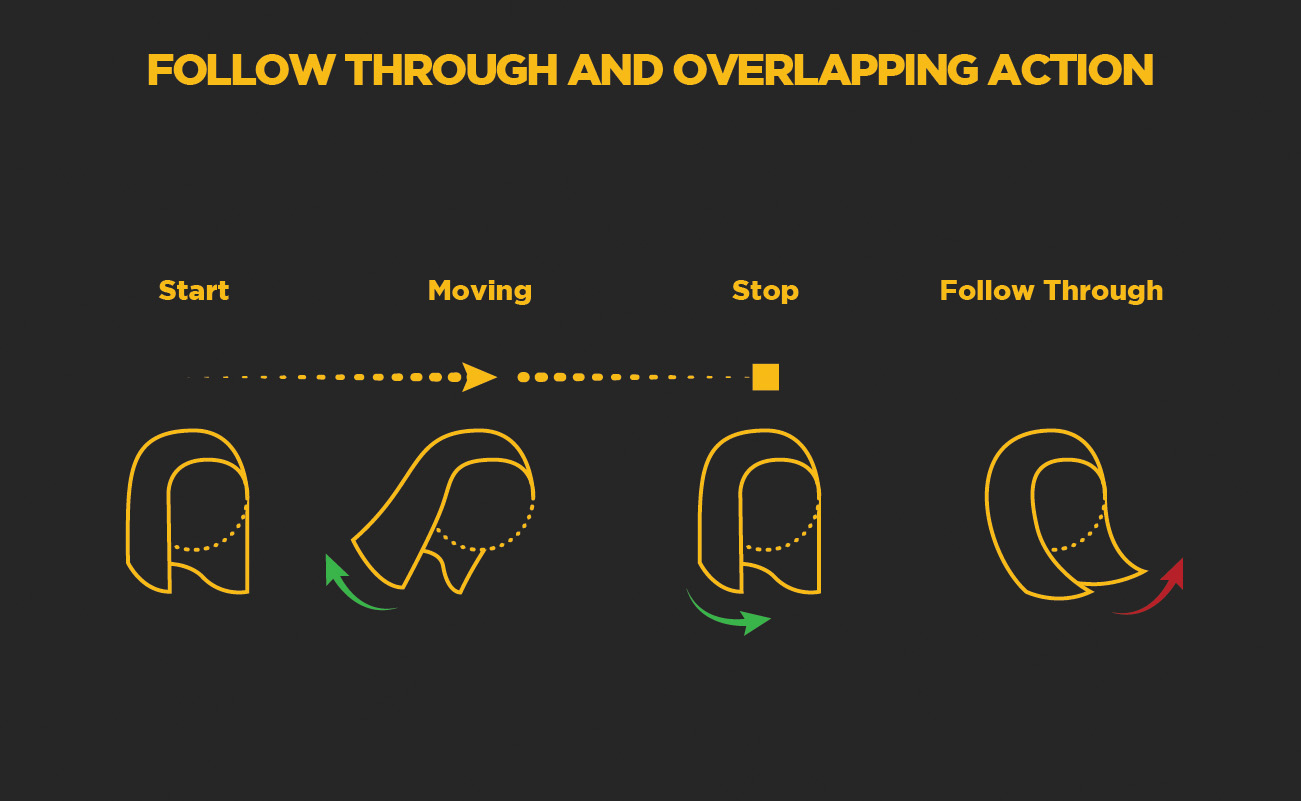

5. Follow Through and Overlapping Action

These principles describe the way in which some objects with flex or joints may move differently to a solid object.

For example, if a person with long hair was to start moving, it hair would flow behind their head. This is also commonly known as ‘drag’. If that person was to then stop abruptly, their hair would swing forward past their head before settling back down.

Overlapping Action is the time delay between these movements. When the person’s head starts to move, the hair doesn’t instantly swing backwards – there’s a short delay first. Again, when they stop their hair doesn’t immediately come to a rest, there’s another short delay whilst the hair swings forward from the perpetual motion before coming to a rest.

6. Ease in and Ease Out

When something is set in motion, it doesn’t immediately start moving - it must start from a standstill and speed up from there. Depending on the object this can happen quickly or slowly. Let’s take a sportscar for example: when it starts to accelerate it has to get faster and faster until it reaches its top speed. It has to ease out of its first position.

When it wants to stop, it doesn’t immediate stop moving either - it has to slow down from its full speed to a stop and ease in to its new position.

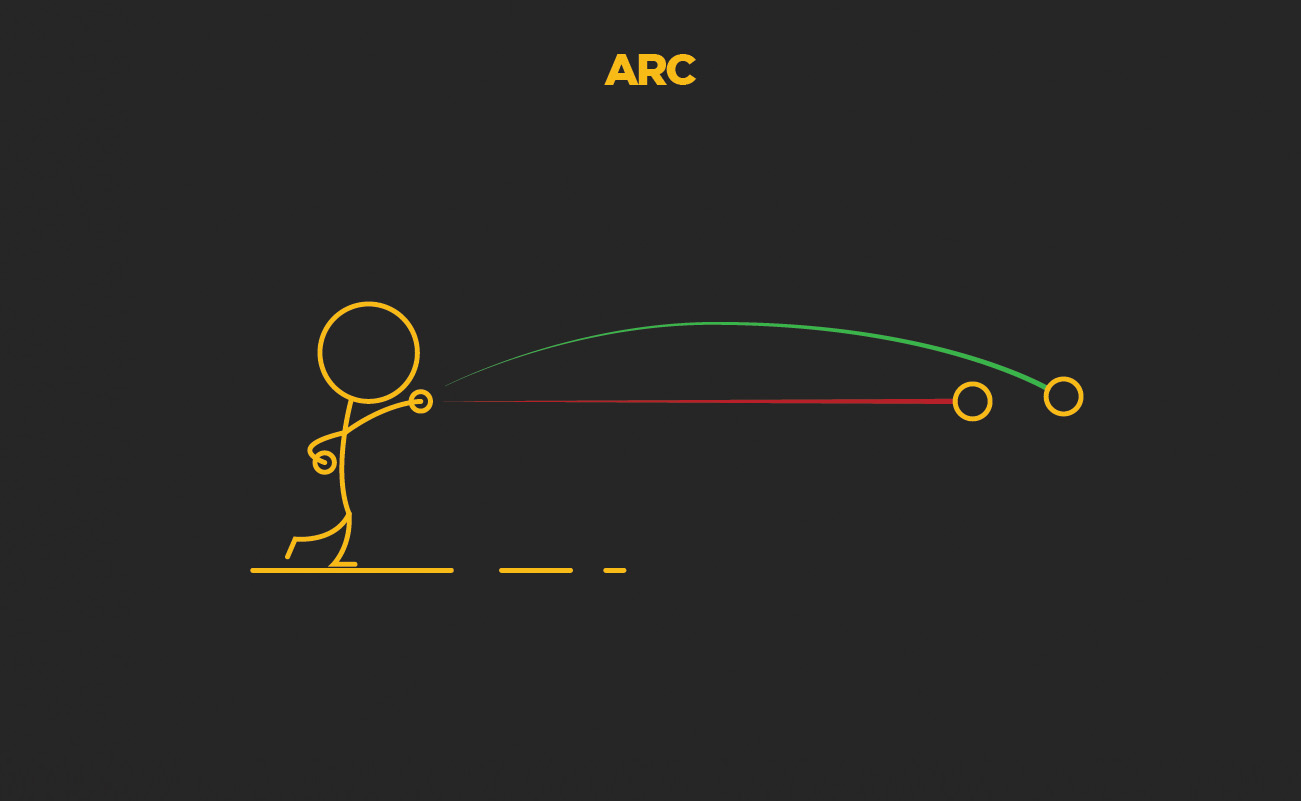

7. Arc

Almost all organic forms move in what we call circular motion, or fluid motion. The opposite of this would be robotic or linear movement. Arcs are used in all types of animation to trick us into believing that it’s behaving in a life-like manner. Think about how a human would walk compared to a robot? The human would walk with ease, slowly bobbing up and down with their arms swinging by their sides. A robot would not move with the same amount of circular motion as it is made up of metal, bolts and joints rather than a human’s muscles. Its walk would be rigid and unnatural, but this is how animators use arcs to demonstrate just how organic the movement should be.

Let’s take the simple example of a ball being thrown. When it leaves our hand, it doesn’t just travel in a straight line, does it? It’s immediately effected by several effects, but one of most important ones is gravity. As soon as we let go of the ball, it’s going to start moving towards the ground. Now how quickly it does this is dependent on many factors like its volume, mass and drag, but luckily, we can use all these features to our advantage in animation. If it were to drop very quickly over a short distance, the ball would appear to be very heavy, but if it continued to sail through the air dropping slowly, we can understand that this one is light.

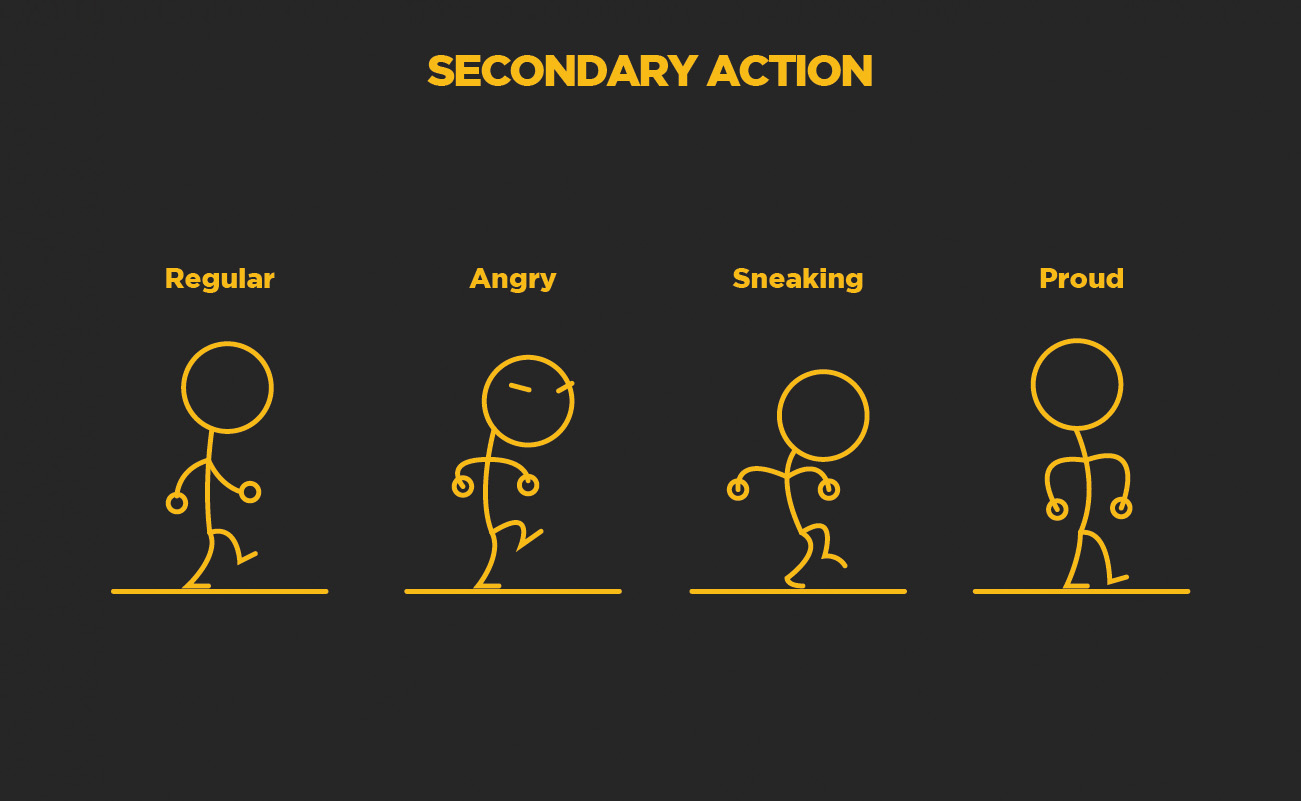

8. Secondary Action

A secondary action is a movement that compliments a main action, that gives it tone, feeling and helps the view understand the manner in which the main action is occurring.

Let’s think about an average person walking. Without too much detail, we can’t really tell what the person this thinking or feeling, but if we add frowning eyebrows, clenched fists, raised knees and stamping feet we immediately get the impression that this character is angry. Raise the arms, open the hands, bend the back and curl the toes – suddenly our character is sneaking about. Puff out the chest, raise the head high, widen the shoulders and our character is now very proud or confident.